Boudoir – The Court Dress of Hungary, the díszmagyar

Another week ended, another Boudoir comes… This week’s Boudoir is going to be special, as I am writing both in English and in Hungarian (the Hungarian will be after the English) – I cannot do to not to write in Hungarian, when I am telling about the court dress of Hungary. So, our dear guest on this very day is no one else but the díszmagyar.

In spite of the popular belief, at least three or four types of Hungarian dress exist: (i) the díszmagyar, (ii) the kismagyar or bocskai, (iii) the traditonal Hungarian costume, and apart from these there are numerous Hungarian national costumes. The kismagyar means a usually black, suit-like garment with Hungarian-style braiding and also Hungarian-style white necktie. This kind of clothes can be worn by both men and women for work or for special occasions like wedding, christening, job inerview, school ceremony, etc. Nowadays the bocskai is becoming popular again, but sometimes with a nationalist political overtone, unfortunately.

The ’real’ court dress – in terms of its classical meaning, like in the case of the Russian and Greek court gowns – was the díszmagyar. The díszmagyar emerged from the traditonal Hungarian costumes of the 16-17th centuries, as well as from Hungarian national costumes. From the Hungarian Reform Era to the Second World War the díszmagyar was the official wear in the royal court (in Buda), in the Parliament, at coronations and balls, on the occasion of the inauguration of a new government, on national holidays and so on. But it is important to mention that the díszmagyar was the attire of the nobility and the royal family – commoners and ordinary people without huge fortune or high political position rarely wore it. (Just to contradict myself: my great-grandmother did have a díszmagyar, though my great-grandparents were not of noble origin, my great-grandfather worked “only” as a Senior Counsellor and my great-grandmother was not even a Hungarian, her family came from Bohemia.)

The díszmagyar for both men and women can be made of various materials, such as velvet, silk, brocade and other exotic cloth from Asia. The colour was not prescribed – though the different parts of the attire should harmonise in colour, of course –, however, following the downfall of the Hungarian Revolution and War of Independence of 1848–49, black became dominating as the symbol of mourning, and vivid colours only returned after the Compromise of 1867. After the First World War and during the Horthy era – when Hungary still was a kingdom – the díszmagyar remained the official court wear, representing the Hungarian indentity and pride. The end of the díszmagyar-era” came with the abolishment of the monarchy and the communist rule after the Second World War. During the socialist era the díszmagyar was nothing but a costume of old times in historical movies.

The díszmagyar for men included a short Hungarian fur coat, the mente, a dolman (and later one of its forms, the atilla), pants and a same colour briefs. A full díszmagyar was worn with high fur cap, the süveg, with boots, necktie, ceremonial sword or sable and with a collection of jewelry. Based on the style of the braiding, the collar and the sleeves, there were different kinds of mente, for example kazinczy, zrinyi, buda. Though it was not mandatory, mente was usually worn only on one of the shoulders – there is even a specific Hungarian phrase for this, ’panyókára vet’.

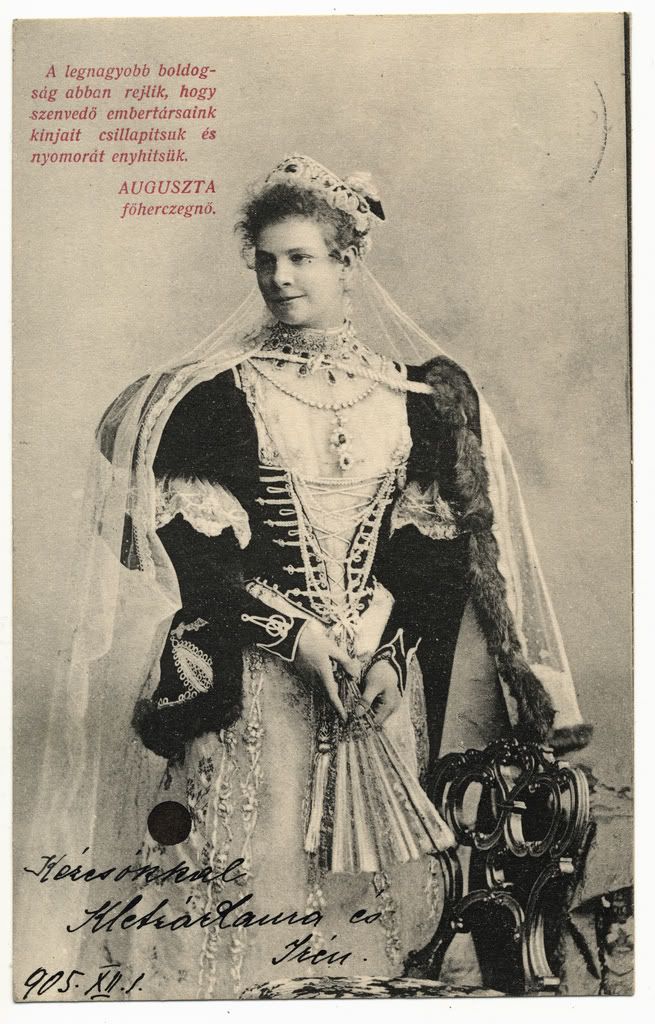

The female version contained a skirt, an apron, a shirt and a shoulder; the latter two became one garb, the derékalj, up to the 19th century. There were no ’shoes code’ or ’jewelry code’, however, at occasions like coronation the best jewelries and a veil were required to wear. At the end of the 19th century, a mente thrown over one of the shoulders – similar to the men’s wear – also became the part of the female gown. The skirts followed the Parisian fashion, except the bustles – there were never ever a díszmagyar with bustle; while the sleeves were usually short and puffy. As for the headdress, the Hungarian-style headdress, the párta, or the bonnet were in use, and at special occasions women wore tiara.

The female version contained a skirt, an apron, a shirt and a shoulder; the latter two became one garb, the derékalj, up to the 19th century. There were no ’shoes code’ or ’jewelry code’, however, at occasions like coronation the best jewelries and a veil were required to wear. At the end of the 19th century, a mente thrown over one of the shoulders – similar to the men’s wear – also became the part of the female gown. The skirts followed the Parisian fashion, except the bustles – there were never ever a díszmagyar with bustle; while the sleeves were usually short and puffy. As for the headdress, the Hungarian-style headdress, the párta, or the bonnet were in use, and at special occasions women wore tiara.

* * *

A közkeletű hiedelemmel ellentétben legalább három vagy négy „magyaros ruha” létezik: (i) a díszmagyar, (ii) a kismagyar vagy másként bocskai, (iii) és a hagyományos magyar viselet; és ezek mellett természetesen ott vannak még a különféle népviseletek is. A kismagyar egy öltönyszerű, többnyire fekete anyagból varrott, magyaros zsinórozású és fehér magyar nyakkendővel viselt öltözéket jelent, amit nők és férfiak is egyaránt hordhatnak. A kismagyar inkább ünnepélyes viselet ugyan – főként esküvőkön, keresztelőkön, iskolai ünnepségeken és állásinterjúkon lehet(ett) vele találkozni –, ám mégis elsősorban az átlagembereknek, a hétköznapi igényeket kielégítendő született meg. Manapság a bocskai megint bekerült a köztudatba, népszerűsége növekszik, de sajnos viseléséhez olykor szélsőjobboldali politikai felhang is társul.

Az „igazi” udvari öltözék – a szó hagyományosan vett értelmében, mint például az orosz és a görög díszruha esetében – a díszmagyar volt. A díszmagyar a 16-17. században hordott hagyományos magyar viseletből alakult ki, de természetesen kölcsönzött elemeket a magyar népviseletből is. A reformkortól kezdve egészen a második világháborúig bezárólag a díszmagyar volt a hivatalos viselet a budai királyi udvarban, az országgyűlés(b)en, koronázásokon és bálokon, az új kormány beiktatásakor, a nemzeti ünnepeken, nemesi esküvőkön és így tovább. Fontos azonban megemlíteni, hogy a díszmagyar viselése amolyan „kiváltság” volt, amit a császári-királyi család tagjai és a nemesek élvezhettek – a közemberek ritkán öltöttek díszmagyart, hacsak nem voltak dúsgazdag mágnások vagy magas politikai pozícióval rendelkező személyek. (Csak hogy ellentmondjak magamnak: a dédanyámnak viszont volt díszmagyarja, holott a dédszüleim nem voltak nemesi származásúak és a dédapám „csak” főtanácsos volt, ráadásul a dédanyám nem is volt magyar, Csehországból származott.)

Az „igazi” udvari öltözék – a szó hagyományosan vett értelmében, mint például az orosz és a görög díszruha esetében – a díszmagyar volt. A díszmagyar a 16-17. században hordott hagyományos magyar viseletből alakult ki, de természetesen kölcsönzött elemeket a magyar népviseletből is. A reformkortól kezdve egészen a második világháborúig bezárólag a díszmagyar volt a hivatalos viselet a budai királyi udvarban, az országgyűlés(b)en, koronázásokon és bálokon, az új kormány beiktatásakor, a nemzeti ünnepeken, nemesi esküvőkön és így tovább. Fontos azonban megemlíteni, hogy a díszmagyar viselése amolyan „kiváltság” volt, amit a császári-királyi család tagjai és a nemesek élvezhettek – a közemberek ritkán öltöttek díszmagyart, hacsak nem voltak dúsgazdag mágnások vagy magas politikai pozícióval rendelkező személyek. (Csak hogy ellentmondjak magamnak: a dédanyámnak viszont volt díszmagyarja, holott a dédszüleim nem voltak nemesi származásúak és a dédapám „csak” főtanácsos volt, ráadásul a dédanyám nem is volt magyar, Csehországból származott.)

Férfiak és nők számára a díszmagyar sokféle anyagból készülhetett, úgymint selyemből, bársonyból, brokátból, posztóból és egyéb egzotikus ázsiai kelmékből. A szín nem volt meghatározva – bár természetesen a különböző ruhadaraboknak összhangban kellett lenniük egymással –, az 1849–49-es forradalom és szabadságharc elvesztése után azonban a gyászt jelképező fekete került túlsúlyba, egészen az 1867-es kiegyezésig. Az első világháború után és a Horthy-korszakban – amikor Magyarország államformája még mindig királyság volt – a díszmagyar továbbra is udvari viselet maradt, és szerepe a szabadságharc utáni időkhöz hasonlóan kiegészült a magyarságtudat képviselésével és hirdetésével. A díszmagyar-korszaknak lezárását a királyság megszüntetése és a kommunisták hatalomra kerülése jelentette a második világháború után. A szocialista uralom alatt a történelmi filmekben már mint csak egy letűnt korszak jelmeze tűnt fel.

A férfiak díszmagyarja mentéből, az alatta hordott dolmányból (vagy később ennek szabott derekú változatából, az atillából), nadrágból és a vele megegyező színű alsónadrágból állt. A díszmagyart a süveg, a csizma, a nyakkendő, a díszszablya és ékszerkészlet – amiből volt „kis” és „nagy” változat is, az alkalom fontosságának megfelelően – tette teljessé. A zsinórozás, a gallér és az ujjak szabása alapján többféle mentét különböztettek meg, úgymint például a kazinczyt, a zrinyit és a budát. Ha volt mente, legtöbbször (nem kötelező jelleggel ugyan) félvállon, azaz „panyókára vetve” hordták.

A férfiak díszmagyarja mentéből, az alatta hordott dolmányból (vagy később ennek szabott derekú változatából, az atillából), nadrágból és a vele megegyező színű alsónadrágból állt. A díszmagyart a süveg, a csizma, a nyakkendő, a díszszablya és ékszerkészlet – amiből volt „kis” és „nagy” változat is, az alkalom fontosságának megfelelően – tette teljessé. A zsinórozás, a gallér és az ujjak szabása alapján többféle mentét különböztettek meg, úgymint például a kazinczyt, a zrinyit és a budát. Ha volt mente, legtöbbször (nem kötelező jelleggel ugyan) félvállon, azaz „panyókára vetve” hordták.

A női változathoz a szoknya, a kötény, valamint az ing és a váll összeolvadásából a 19. századra kialakult derékalj tartozott. Sem a cipőre, sem az ékszerekre nem vonatkozott semmilyen megkötés, ez többnyire a viselő pénztárcájához volt szabva, de természetesen a koronázásokon a legjobb ékszerek és a fátyol is elvárt kiegészítők voltak. A 19. század végére a női díszmagyar kiegészült a férfiakhoz hasonlóan általában félvállra vetve hordott mentével. A szoknya követte a párizsi divat változásait, biedermeier stílusú vagy éppenséggel krinolinnal viselt díszmagyarok egyaránt előfordultak. Kivételt a turnűr vagy fardagály jelentett, amely szerencsére nem tudta befolyásolni a ruha formáját. A ruhaujj rendszerint rövid és buggyos volt. Ami a fejdíszeket illeti, a nők többnyire pártát vagy főkötőt hordtak, de különleges események alkalmával előkerültek a tiarák és egyéb diadémok is.

* * *

As for my personal opinion, the díszmagyar is my favourite court dress. Not because I am Hungarian, but because aside from that it is really-really beautiful, it was made the court dress of Hungary ’voluntarily’ – not by the order of the ruler like in the case of the Russian and the Swedish ones, it was not made by only one person like the Greek one, but it became the court gown because whole of the nobility wore it voluntarily, to express their pride to be a Hungarian.

Kicsit személyesebb vizekre evezve, a díszmagyar a kedvenc udvari díszruhám. Nem azért, mert magyar vagyok, hanem mert attól eltekintve, hogy csodálatosan gyönyörű, a ruha „önkéntesen” lett a magyar díszviselet – nem az uralkodó írta elő, mint az oroszt és a svédet, és nem egyetlen ember alkotta meg, mint a görögöt. Azért lett díszviselet, mert az egész nemesség önkéntesen hordta, hogy kifejezzék: büszkék arra, hogy magyarok.

by Alla / írta Alla

Source, link / Forrás és hivatkozás: Tompos Lilla: A díszmagyar; images / képek

Comments

Post a Comment